NUTTALLBURG

The history of the community and mine at Nuttallburg is a tale of several men and their brushes with fortune. The first of these men was the coal operator from which it took its name: a determined, self-made man named John Nuttall.

John Nuttall first saw the light of day in Accrington, England on April 9, 1817. When his father died while John was only three years of age, the family fell upon desperate times. One by one he and his brothers entered the mines of England as soon as they were big enough to convince the owners they could carry their weight. By the age of 11, John Nuttall was doing a man’s job in the mines.

The young boy soon demonstrated an uncanny understanding of the complex workings of underground mining. But he was not content to live out his life working for others. At the age of 17, he made a vow to himself that he would save enough money to leave England and seek his fortune in the promised land of America. It was not an easy vow to fulfill and the challenge would soon become ever greater as the years went by. Marrying young, he was the father of three children by the age of 32, but he remained true to his dream. In May of 1849, he left his family in England and set out for New York. Within a year, he earned enough to bring his family to his new home.

Tragedy struck just when he believed his dream was finally coming true. In 1853, his wife Elizabeth died, leaving him with four young children to care for and raise. Undaunted by the new challenge, Nuttall moved his family to Pennsylvania, where it was rumored a new railroad was opening up an untouched coalfield. There he made a series of smart business moves that led him to become the owner of a small mine he named Nuttallville. To this new home, he moved his children and his new wife, Ann.

Nuttall proved to be extremely successful in his Pennsylvania mining endeavors but he never lost his boyhood urge to conquer new horizons. When he heard the C & O Railway was about to open up another untouched coalfield in the New River Gorge, he was among the first investors to rush to the area. Forty-five years of hard work had done nothing to dampen his enthusiasm for adventure, and the 53-year-old Nuttall was fascinated with the potential of this new land for development.

On his first visit to the area, Nuttall noticed that the tavern where he was staying was burning an especially high grade of coal. Investigating the source, he learned that it was taken from a coal seam almost four feet thick that ran through the mountain directly above the proposed route of the C & O line. Convinced that there was a new fortune to be made, Nuttall quickly bought up as much property as possible for the going price of $1.00 an acre.

By the fall of 1870, Nuttall was at work in the Gorge getting his mining operation in place. The new mine was ready even before the C & O line was complete. His new operation, which promised production of as much as 500 tons of coal per day, was christened Nuttallburg. The mine began making a profit as soon as the C & O Railroad began shipments in 1873.

In 1882, Nuttall formed the Nuttallburg Coal & Coke Company with equal partnerships divided among his sons, son-in-law Jackson Taylor, and his mine boss William Holland. The other partners were to pay Nuttall a 10-cent royalty on all coal mined plus an additional royalty of 2 cents per ton to repay his investment in houses and equipment. However, the mine was so profitable that 12 years later Nuttall cancelled the royalty because he felt the obligation was fulfilled.

By 1893, the community of Nuttallburg had grown to include over 300 residents. Although John Nuttall died in 1897, the town would continue to prosper under the careful guidance of the Nuttall family for the next three decades.

By 1919, many believed that the Nuttallburg Mine was on the verge of working out. The expected life of a mine at the turn of the century was approximately 30 years before it advanced too far beneath the mountain for it to remain profitable to remove the coal. Therefore, area residents were not surprised when the Nuttall family decided to sell out in 1919. However, what did surprise them was that the man who purchased the Nuttallburg Mine was the famous automobile millionaire, Henry Ford.

One newspaperman of the era was so surprised at the deal that he sarcastically remarked that Ford would be better off to use the old workings for storing auto parts than for mining coal.

However, Ford was not a man to be shaken by the challenge and he immediately instigated a tidal wave of changes at the Nuttallburg operation. Within two years after he had taken control, the mine had abandoned pick mining completely and instead was running four mining machines full-time. With an employment of only 49 men, the Nuttallburg mine was producing over 45,000 tons a year.

Great excitement struck the area when it was announced that Ford would visit the property in person during October, 1921. Accompanied by his son Edsel and several top officials of the company, Ford arrived at the Nuttall station that morning in his personal railroad car and set off for a tour of the mine and town. The millionaire left no part of his property unvisited. At the mine, Ford and his son donned overalls and set off underground. The workings at Nuttallburg averaged only a little over three feet in height and in some places it was necessary to crawl, but the 60-year-old Ford took the challenge in stride. He did not stop until the entire party reached the working face of the mine over three miles beneath the mountain.

Following his trip through the mine, Ford went on to visit every area of the community from the homes, to the schools, to the playgrounds. In every location, he was full of questions for residents and suggestions for improvements.

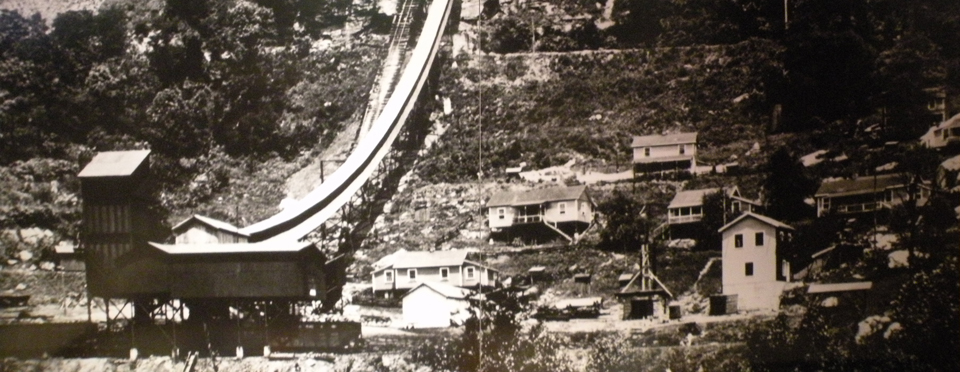

The famous auto maker must have been pleased with what he saw because he continued his investments at Nuttallburg. In 1923, he financed construction of the Henry Ford Tipple which was the largest incline in the world at the time of its completion.

The visit of Henry Ford to Nuttallburg aroused excitement but it was nothing compared to another development soon afterward. Even those who had been indifferent to the visit of the millionaire were fascinated to learn that a fortune of their own might well be there for the taking in the coal town.

This excitement came about in connection with William Holland, a former partner of Nuttall and later owner of his own mining company in the New River community of Winona. It was the home of this man that fed the legend of Nuttallburg Gold.

After making his fortune in the mines, Holland built a home for his family on property he owned at Nuttallburg. Although he continued to live in this house until his death in 1918, few men ever got to know him well. Holland was an eccentric man with a deep mistrust of people. Apparently this mistrust extended to bankers, because it was later discovered that he had placed a large part of his fortune in glass jars and buried them on his property. This eccentric secret he shared with no one, not even his five children.

Legend maintains that when Holland was struck by a severe heart attack in 1918, he tried desperately to convey some message to his children as he lay on his deathbed but he was too weak to make himself understood. With no knowledge of the hidden store of bank notes and gold coins, his heirs sold the property to the Inland Steel Company in 1921.

In his declining years, Holland had employed a gardener named Dixon to help keep up the house and grounds and the new owners kept the man in their employ after the property was sold. While fixing up the flower beds in anticipation of the new owner’s arrival, the gardener made a discovery that would earn him a lasting place in New River Gorge history: for deep beneath an old flower bed, Dixon discovered two half-gallon jugs of treasure. The first jar was filled with old British sovereigns and American gold coins of every denomination. Amazed, the old man pulled out $5, $10 and $20 gold pieces from this half gallon jar. The second jar was apparently buried later but was crammed full of tightly rolled old American $50 bills.

The gardener may have been a simple man but he was not a foolish one. Taking his newly found treasure, he quickly disappeared from the area, telling only a few close friends of his good fortune.

Shortly afterward, the house came into the possession of William Nicholson, Superintendent of the Stover Coal Company. The new owners had no clue that their new home might well be a house of treasure but they would soon find out. When Nicholson moved into the house, he immediately hired workers to begin bringing it back to its former glory. Plumbers removing a partition inside the house discovered a metal box hidden in the studding. When it was opened the box was found to contain $20,000 in gold coins. Shortly afterward, a carpenter working in the house suddenly disappeared without notice amid rumors that he had discovered an additional $20,000 in another hiding place.

Each new discovery convinced the Nicholsons that the bulk of the treasure had been found but treasure continued to turn up in unexpected places. A man named Matthew Dickson unearthed another $490 in gold in the old greenhouse. Shortly afterward, five other carpenters working on the house found several glass jars of treasure hidden in the cellar. The $21,000 in bank notes and gold English sovereigns were quietly divided up between them. Although they tried to keep this windfall a secret, the news soon leaked out.

When the Holland family learned of the discoveries made on their father’s property, they sued to file legal claim to the wealth, but the effort proved unsuccessful. Legally, the house and all its contents had been sold to the new owners, and by that time the Holland treasure was spread far and wide.

After learning that they retained legal claim to whatever treasure remained, the Nicholson family began to search in earnest. By the time the search ended, it was said that there was not one inch of the house that had not been searched nor one foot off the large yard in which the soil had not been turned. If any further discoveries were made, the Nicholsons kept their secret much more tightly than those who had gone before.

Today, all that remains of the Holland house is a set of foundations beneath the vegetation covering the now deserted town of Nuttallburg. If treasure is still hidden there, its location remains the final secret of the now legendary New River miser, William Holland.

Click HERE to download and read “The Life of John Nuttall” – written by his grandson, John Nuttall.